Did you know that a parasitic infection can put a pregnancy at risk of serious complications? Toxoplasmosis, caused by Toxoplasma gondii, a little parasite that uses cats as its definitive host, can sometimes disrupt normal fetal development. But what factors affect the chance of transmission from the mother to the fetus, how can toxoplasmosis be diagnosed, and what can be done to address the issue? Keep reading to find out.

Toxoplasma gondii (T.gondii) is a parasite that belongs to the Phylum Apicomplexa. We can find it in all world regions, especially tropical climates. Therefore, it is estimated that one-third of the human population has been infected with T.gondii worldwide. It is an obligate intracellular parasite, and as we will see later, its life cycle consists of three different forms. It infects most warm-blooded animals, including humans, sheep, goats, and chickens, which act as intermediate hosts. Cats and other members of the Felidae family are its definitive hosts, and they play a significant role in the parasite’s life cycle and transmission. The disease caused by T.gondii is called toxoplasmosis. It is considered a zoonotic disease and is usually transmitted through the fecal-oral route.

Created in Biorender.com

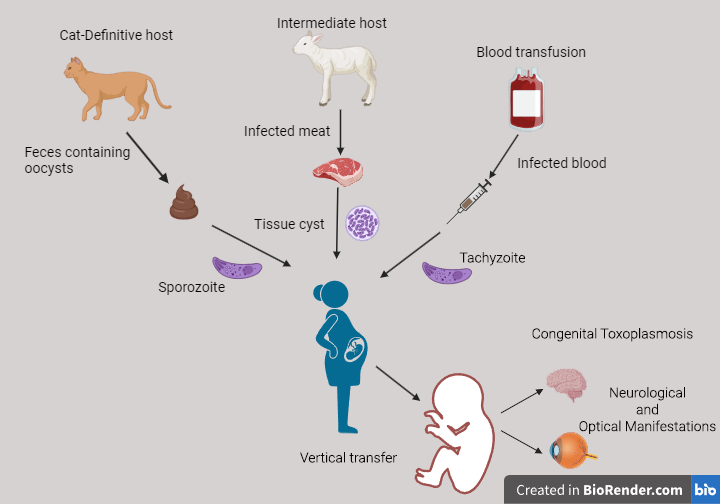

Humans can contract Toxoplasma gondii via the following mechanisms:

1) eating raw or undercooked meat that has been infected with the parasite,

2) ingesting the parasite after coming into contact with contaminated cat feces

3) transmitting the parasite from an infected mother to her fetus during pregnancy, or much less frequently through

4) receiving blood transfusions from an infected donor, although this happens less frequently.

Most of the time, people cannot identify how they got infected. However, data shows that the most common route of transmission is the consumption of contaminated food.

Toxoplasmosis is not considered dangerous for immunocompetent individuals. Most people remain asymptomatic or develop mild symptoms that resolve quickly. However, contracting T.gondii during pregnancy can become serious if the parasite crosses the placental barrier.

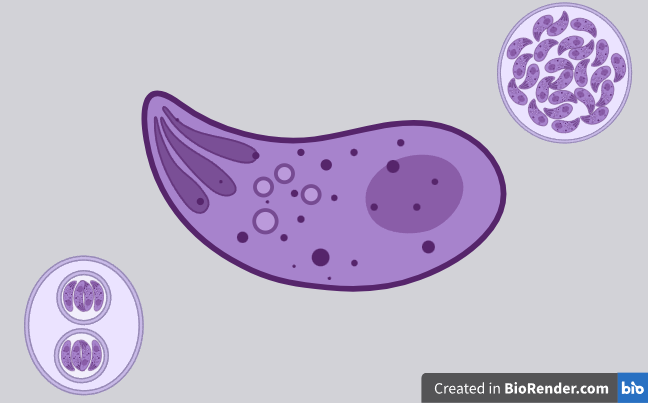

Before we learn about what happens during pregnancy, let’s look at the life cycle of T.gondii. There are three forms of this parasite: tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and sporozoites. A cat (the definitive host) can ingest T.gondii from infected feces in the soil or by consuming an infected animal (e.g. a rodent). Once inside the cat, the parasite starts multiplying sexually in the small intestine. Afterward, it is excreted to the environment in the form of oocysts, which contain sporozoites that can be found in feline feces. If an intermediate host, such as a human, ingests these oocysts, the asexual life cycle of the parasite begins. The sporozoites get out of the oocysts and transform into tachyzoites. Tachyzoites multiply fast inside nucleated host cells. They can then escape the host cell cytoplasm and enter the circulation. This way, they can reach target tissues, such as the brain, eyes, or muscles, where they transform into bradyzoites. Bradyzoites are highly infectious and can survive in a dormant state inside cysts. These cysts remain there indefinitely or may later get reactivated in case of immunosuppression.

As we said before, getting infected with T.gondii during pregnancy may cause serious adverse events to the growing fetus, and this depends on the stage of gestation. The transmission from mother to fetus is called vertical transmission, and it leads to congenital toxoplasmosis. Fetal infection may occur if the woman:

a) has been infected shortly before getting pregnant or has acquired the parasite during pregnancy. Therefore, there is a possibility of parasitic transmission to the fetus or

b) had been infected in the past. But, due to receiving certain treatments during pregnancy (e.g. corticosteroids), she becomes immunosuppressed. This way, the parasite is reactivated from dormancy and may be transmitted to the fetus.

During the first trimester, there is a low chance of parasite transmission. However, an infection during this period might eventually lead to a miscarriage. That happens because the fetal immune system is not yet developed to fight off infections. During the second trimester, congenital toxoplasmosis can cause serious consequences on fetal development and induce a variety of conditions, like retinochoroiditis, microcephaly, hydrocephalus, or mental retardation. It is also associated with a miscarriage, premature birth, or stillbirth. If the infection occurs later in the pregnancy course and closer to delivery, there is a higher chance that the mother passes the parasite to the fetus. In this case, an asymptomatic fetal infection is more likely than in earlier stages. However, there is still some risk that the offspring’s health might be affected later in life. For example, there is a correlation between toxoplasmic infection and neurological or optical manifestations that show up when the child gets older.

Once T.gondii is inside the fetal circulation, it can infect particular cells, such as monocytes and dendritic cells of the immune system. It then uses them as carriers to access other body regions, such as the brain or the eyes. Researchers try to determine what factors contribute to the infection passing to the growing fetus. For example, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β, although help fight the toxoplasmic infection in the mother’s body, they enable the transmission of the parasite through the placenta to the fetus. That happens via a mechanism that increases the adhesive abilities of infected monocytes to the placental cells and thus helps them move toward the fetus. Other studies have tried to decipher if the different levels of sex hormones, such as 17-β estradiol (E2), progesterone, or prolactin, either promote the T.gondii infection or protect the fetus by regulating the immune response against the parasite at different stages of pregnancy.

A pregnant woman may not notice a toxoplasmic infection since the symptoms are mild. For instance, there might be a sore throat or a headache that only lasts a few days. That makes it difficult for the woman to suspect something is wrong. Therefore, to avoid the aforementioned undesirable consequences of congenital toxoplasmosis, pregnant women must undergo frequent blood tests to check for an infection. Tests that measure the levels of the specific IgG and IgM antibodies against the parasite in the woman’s serum are a good starting point for recognizing asymptomatic cases. Anti-Toxo IgG antibodies are produced by the immune system and can be detected around 2 weeks after infection. These antibodies remain in the serum for a long time and help us define if someone has been infected with the parasite in the past. Anti-Toxo IgM antibodies appear earlier than IgG antibodies during an infection. These remain at high levels for a few weeks and then gradually decline. That helps us determine if someone is currently infected with the parasite.

Although there is no definitive treatment against toxoplasmosis, the expecting mothers are usually treated with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, or spiramycin when there is an early diagnosis. However, there are still questions that need answers. For example, which of the available options is more effective in preventing congenital toxoplasmosis in the fetus, and at what time point is it better to initiate treatment for more effective results? It seems that the risk of developing serious long-term consequences, such as blindness or neurological and cognitive disabilities, is reduced when the infants get the correct treatment. Even if the symptoms of the disease do not disappear completely, their severity is improved profoundly after treatment. Another issue that needs addressing is the occurrence of unwanted side effects of these treatments in infants who are suffering from congenital toxoplasmosis. Usually, complications such as neutropenia, hepatotoxicity, and hypersensitivity reactions accompany these medications. Moreover, since these treatments cannot eliminate the pathogen, there is still a chance of parasite reactivation in the future that may affect the infant’s neurological development.

From all of the above, it is clear that there is no perfect solution to battle toxoplasmosis once an expecting mother is infected, and there is no vaccine for preventing the disease in humans. The currently available treatments cannot always hinder the clinical manifestations in the infant and can also cause unwanted side effects. So, it seems that the most effective method of reducing the risk of complications is to prevent toxoplasmic infections in the first place. This can be achieved via preventive measures. Women who are planning to have a child must be educated about the dangers of contracting the parasite. Expecting mothers should clean their hands thoroughly, wash fruits and vegetables before consumption, freeze meat before use or cook it at high temperatures to kill any cysts that might be present, and always be cautious when handling a cat’s litter.

Sources:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11202031/pdf/cimb-46-00341.pdf https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7954850/pdf/nihms-1642405.pdf https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9862191/pdf/tropicalmed-08-00003.pdf

https://www.theveterinarynurse.com/content/clinical/toxoplasma-gondii-the-facts/