One day, you woke up with a mild irritation on your arm. The skin was red and itchy. You paid no attention. But the next day, you noticed more bumps filled with pus. It looked concerning, so you decided to check it out with your dermatologist. The doctor collected a sample from the wound and sent it to the lab for further testing. A few days later, the doctor informed you that you had a Staphylococcus aureus infection and prescribed you antibiotics.

There are hundreds of bacterial species capable of causing infections in humans. So, how did the laboratory staff determine that the microbe that caused your infection was Staphylococcus aureus? Read below to learn about some basic tests scientists execute to identify the particular species behind a bacterial infection. In this article, we will focus on a broad category of bacteria, known as Gram-positive cocci, which is only one of the different groups of bacteria existing in nature.

Gram-Positive Bacteria

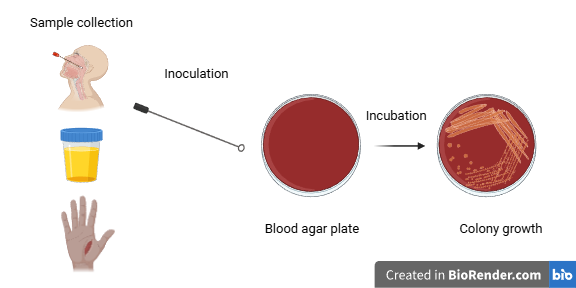

Scientists working in a laboratory use samples taken from patients, for example, a urine specimen, a throat swab, or a sample removed from a wound. They inoculate the sample into petri dishes containing nutrients and then incubate them for 18-24 hours. Note that there are various culture media that differentiate between bacteria. After bacterial colonies have grown on the plates, scientists start testing to identify the particular bacterial species.

Let’s imagine we are working in a laboratory and we have to identify the bacterial species that has formed colonies in the culture plates. We first have to categorize the infecting agent based on its cell wall structure and the cell’s shape.

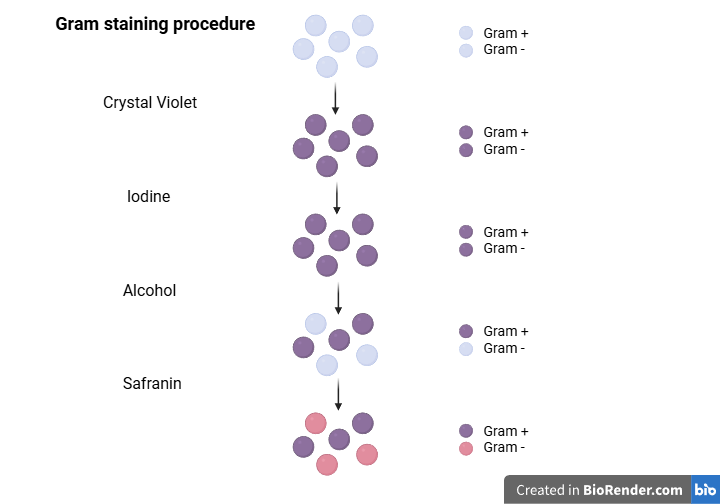

Gram staining is a technique that helps us classify bacteria into two broad groups (Gram-positive and Gram-negative) based on their color under a microscope. Gram-positive bacteria appear purple, while Gram-negative bacteria appear pink. The thick peptidoglycan cell wall in Gram-positive bacteria traps a dye (Crystal Violet), which gives the cells a purple color. On the other hand, the large number of lipids present in the plasma membrane of Gram-negative bacteria allows this dye to be washed out, making the bacteria colorless. Subsequent use of another stain, usually safranin, gives the Gram-negative bacteria a pink color.

Gram-Positive Cocci

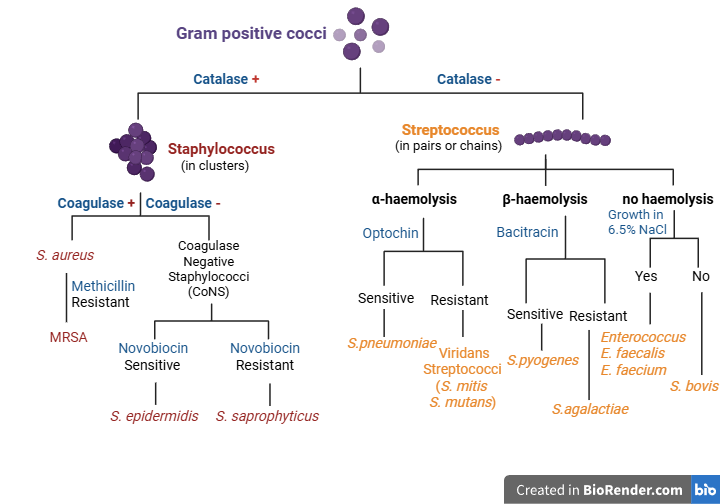

Gram-positive bacteria may differ in shape; cocci are spherical, while bacilli are rod-shaped. As we mentioned earlier, we will focus on Gram-positive cocci, since some of them cause frequent serious nosocomial infections that can put patients’ lives in danger. So, let’s suppose we have concluded that the infecting agent in our sample is a Gram-positive coccus, based on microscopy and Gram-staining. Gram-positive cocci can be divided into two large groups, Staphylococci and Streptococci, as we can see in the picture below. To reach a conclusion about the particular species the microbe in question belongs to, specific tests targeting bacterial biochemical characteristics are needed.

Catalase test

As a first step, we perform a catalase test. The Catalase test determines whether the bacteria can produce an enzyme called catalase. Catalase converts hydrogen peroxide to oxygen and water to protect the cells from the potential toxic effects of hydrogen peroxide. The reaction catalyzed by this enzyme is shown below.

2 H2O2 + Catalase → 2H2O + O2

To test the catalase-producing properties of bacteria, we use a drop of hydrogen peroxide on a slide. We then mix it with a bacterial colony that has grown in the culture plate. If we see bubbles on the slide (positive catalase test), it means the species in question produces catalase (catalase-positive species). If no bubbles are observed, the catalase test is negative, and the bacterial species is catalase-negative. The catalase test result helps us categorize the infecting agent as Staphylococcus or Streptococcus. A catalase-positive test result means the microbe is a Staphylococcus; otherwise, it is a Streptococcus. Staphylococci are cocci that usually form clusters.

Catalase-positive cocci

Let’s suppose the catalase test points toward Staphylococcus, and later on, we will come back to Streptococci. Further testing is needed to determine the exact Staphylococcus species that is causing the infection. The next step is to do a coagulase test.

Coagulase test

Coagulase is another enzyme that is not produced by all Staphylococcal species. Therefore, it helps us distinguish between them. Coagulase has a similar function to thrombin, which helps our blood clot. It can convert fibrinogen to fibrin and form clots. To perform the coagulase test, we mix a sample of bacterial colonies from the culture plate with the appropriate reagents on a slide. If coagulase is present, characteristic agglutination (visible clumping) will occur. A coagulase-positive test result indicates the presence of the well-known microbe Staphylococcus aureus, although there are some exceptions that we will not concern ourselves with. Conversely, if the coagulase test is negative (absence of clots), we have a Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) that requires further testing for its final identification, as we will see later.

Coagulase-positive cocci

Staphylococcus aureus is a common microbe found naturally on the surface of our skin or mucus membranes. However, if Staphylococcus aureus enters the skin or bloodstream and colonizes other tissues, it can cause infections. This can occur in the community or in hospital settings. Even though it does not normally pose a threat to immunocompetent individuals, it can cause serious complications, e.g., pneumonia or sepsis, and become fatal if the infection is not managed effectively. One type of Staphylococcus aureus can be even more dangerous. This is Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which doesn’t respond to certain antibiotics. MRSA is typically resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics, such as penicillins and cephalosporins. This is attributed to its beta-lactamase-producing properties. These are enzymes that target the inhibitory activity of the above antibiotics. This way, MRSA keeps synthesizing its cell wall, thus surviving and multiplying in these conditions.

Coagulase-negative cocci

Now, we will focus on the other major group, Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci. To identify the exact species within this group, further testing is needed. For this purpose, we will employ some antibiotics. Let’s see how antibiotics can assist us in this process.

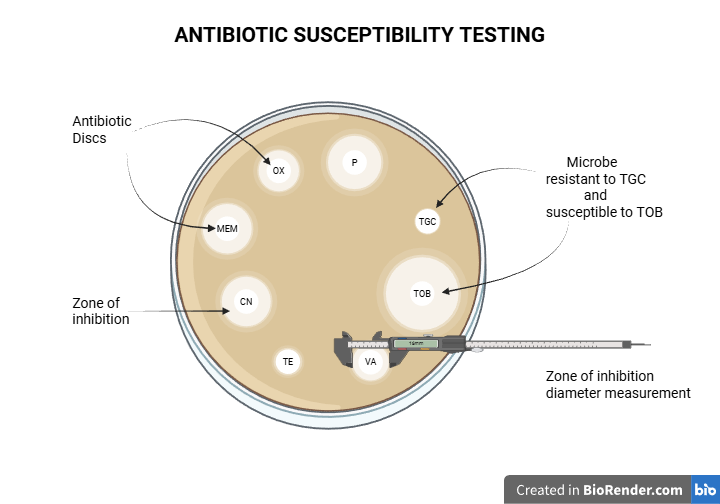

Generally, to determine if a bacterial infection can be treated with a specific antibiotic, we perform an antibiotic susceptibility test. Bacterial colonies are cultured on a plate containing antibiotic discs. If the bacteria are sensitive to an antibiotic, a clear zone of inhibition will appear around the corresponding disc. This means the antibiotic exerts its inhibitory effect and does not let the bacteria grow near it. Conversely, the absence of a zone of inhibition means the microbe is resistant to the antibiotic, thanks to its cells’ defensive mechanisms. In practice, even if a zone of inhibition is present, we typically measure its diameter and compare it to standardized charts to determine if the microbe is sensitive.

Novobiocin susceptibility test

To distinguish among CoNS, we use the Novobiocin antibiotic. Novobiocin exerts its role by inhibiting an enzyme participating in DNA replication. Therefore, we will incubate the microbe in question with a Novobiocin disc to test whether the antibiotic inhibits growth. Growth in the presence of Novobiocin means that the species in question is Staphylococcus saprophyticus, which is Novobiocin-resistant. The absence of growth around the antibiotic means that the species in question is Staphylococcus epidermidis, which is susceptible to Novobiocin.

Staphylococcus saprophyticus is part of the normal flora of organs such as the urethra or cervix, and commonly causes urinary tract infections in sexually active women. Staphylococcus epidermidis is naturally found on the skin, but can enter the body and cause infections, usually through the use of medical devices, such as catheters or central lines. Staphylococcus epidermidis is an opportunistic pathogen and is one of the most common causes of nosocomial infections.

Catalase-negative cocci

Since we learned about the basic tests that distinguish among Staphylococcal species, we will now focus on the other group of Gram-positive cocci, Streptococci. Streptococci are catalase-negative cocci that usually form chains instead of clusters. One useful way to distinguish them is to examine the type of hemolysis these bacteria cause when cultured on a blood agar plate.

Hemolysis of blood agar

Hemolysis is the destruction of red blood cells. Streptococci produce hemolysins, enzymes that cause hemolysis. So, if Streptococci are grown on a blood agar plate, they will destroy the red blood cells. The pattern and extent of hemolysis differ among Streptococcal species, as we will see below.

α-hemolysis

Alpha or α-hemolysis is partial hemolysis. Species with the ability to cause α-hemolysis produce hydrogen peroxide that oxidizes blood agar’s hemoglobin to methemoglobin. As a result, a green color appears around the bacterial colonies. Well-known species that cause α hemolysis are Streptococcus pneumoniae and the Viridans group, which includes Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus mutans.

Optochin susceptibility test

To distinguish between Streptococcus penumoniae and Viridans Streptococci, we utilize their variable response to Optochin. Optochin is an antibiotic that targets the membrane ATPase, preventing ATP synthesis. The bacterial colonies are incubated with an Optochin disc. If bacterial cells do not grow in the presence of this antibiotic, then the species in question is Streptococcus pneumoniae, which is susceptible to Optochin. If, on the other hand, bacterial cells are grown around the antibiotic, it means they can overcome Optochin’s mechanism of action. These Optochin-resistant bacteria belong to the Viridans group, with common representatives being Streptococcus mutans or Streptococcus mitis.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is one of the most common causes of pneumonia in the community, particularly in infants or older individuals with risk factors. Conversely, Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus mitis are both found in the oral cavity and are not concerning unless they enter the bloodstream, where they can cause cardiac damage.

β-hemolysis

Beta or β-hemolysis is another type of hemolysis that is characterized by the complete destruction of red blood cells surrounding the colonies. This effect is caused by two hemolysins, hemolysin O and S. More specifically, hemolysin O is inactive in the presence of oxygen. Therefore, when β-hemolytic Streptococci are cultured in anaerobic conditions, where both O and S hemolysins are active, hemolysis is even more pronounced. Well-known species that cause β-hemolysis are Streptococcus pyogenes, which belongs to Group A Strep (GAS), and Streptococcus agalactiae, which belongs to Group B Strep (GBS).

Bacitracin susceptibility test

To distinguish between Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus agalactiae, we use the antibiotic Bacitracin, which targets peptidoglycan synthesis. If Bacitracin prevents bacterial growth, then the microbe in question is Streptococcus pyogenes (Bacitracin-sensitive). If no zone of inhibition appears around Bacitracin, the microbe in question is Streptococcus agalactiae, which is Bacitracin-resistant.

Streptococcus pyogenes is the responsible agent for strep throat, a common type of pharyngitis in children that is highly contagious. Such an infection can manifest in less common but serious complications if left untreated. Streptococcus agalactiae colonizes the genital tract of many women without causing symptoms. However, its transmission becomes possible during pregnancy or delivery, which can become dangerous for the health of the unborn child or newborn, respectively.

No hemolysis

Apart from α and β-hemolytic Streptococci, there is another Strep group that does not cause hemolysis. However, it might cause a slight discoloration of the culture medium. In this case, the possible species are known as gamma or γ-hemolytic. These include members of the Enterococcus genus, formerly known as Group D Streptococci or another Streptococcus group, such as Streptococcus bovis.

Growth in NaCl 6.5%

To distinguish among Enterococci and other non-hemolytic Streptococci, we need to perform a salt test. We incubate these bacteria in the presence of 6.5% NaCl to differentiate between species tolerant of high salt concentrations and those intolerant, reflecting variations in their adaptation to osmotic fluctuations. Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium are among those able to grow in high-salt concentrations. The absence of bacterial growth in these conditions points towards other non-hemolytic Streptococci, such as Streptococcus bovis.

Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium are the most common Enterococci species. They colonize the gastrointestinal tract and are responsible for many nosocomial infections. Streptococcus bovis includes many Streptococcal species that have been implicated in cases of bacteremia, endocarditis, or colon cancer.

Sources:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470553/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441868/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563240/