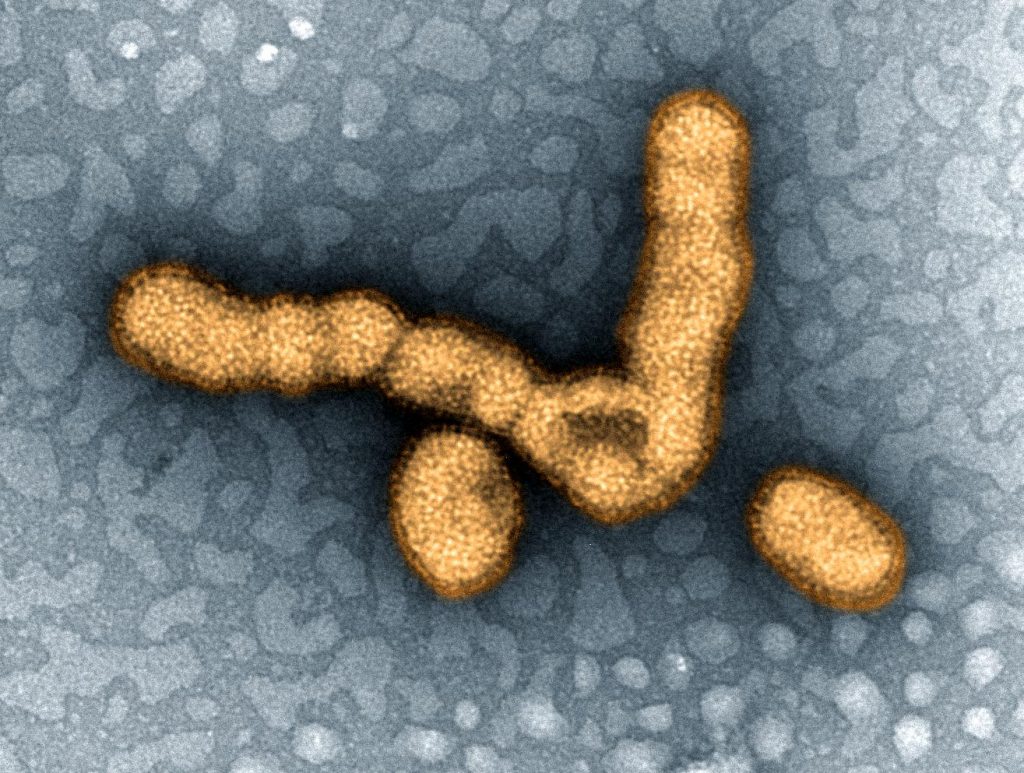

Viruses are microscopic parasites whose size belongs to the nanometer scale. They can invade the cells of other organisms in order to reproduce, since they don’t have the ability to do that independently, outside of their hosts.

You might be familiar with the viruses infecting people but all the living organisms on our planet are susceptible to viruses. There are viruses against animals but also against plants or bacteria, the latter known as bacteriophages. Therefore, we realize that different viruses affect different organisms. For example, the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) attacks tobacco and some other plants, but it cannot infect animals. Viruses might possess features that enable them to infect certain species. Poliovirus is an example that affects closely related species, and more specifically, primates. However, it is very common for viruses to acquire changes, making it possible for them to cross species boundaries and infect species that weren’t previously their hosts, as was the case with the recent coronavirus.

No matter the case, you have to keep in mind that not all viruses result in life-threatening infections. Some of them can cause mild symptoms or go unnoticed. There are even cases when a virus can live inside its host for years without causing any trouble. Of course, though, many infections can be very serious and even deadly.

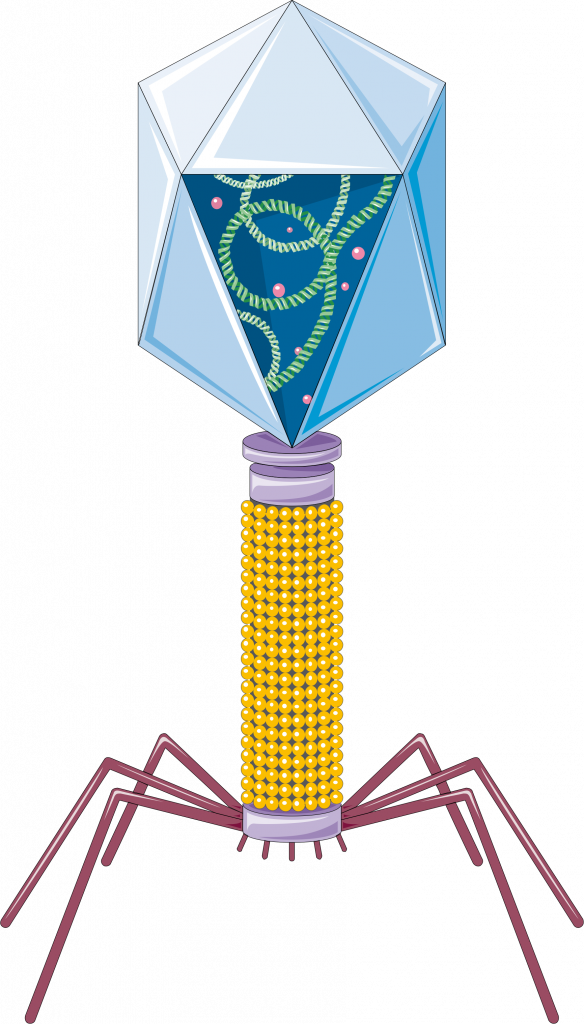

Structure

How are viruses structured? They certainly don’t consist of cells. However, they share the same biomolecules as all the living organisms. They protect their genetic material inside their viral particle, called virion. Their genetic material can be either DNA or RNA and either single-stranded or double-stranded. The types of nucleic acid are usually used as criteria to classify viruses in categories to help us study them and understand how they work. The genetic material is enclosed within a capsid. The capsid is a coat consisting of multiple copies of one or a small number of different protein subunits that are arranged in specific architectures. Outside the capsid, there can be a viral envelope, which is basically a phospholipid bilayer, resembling the structure of cellular membranes, but it is not present in all viruses. Enzymes that are necessary for viral reproduction in the host can also be found inside the virion. The viral nucleic acid contains a small number of genes that code for capsid proteins or enzymes. However, viruses can in no way multiply by using only molecules of their own. They require the existence of their host’s cells. This way they can direct the cellular machinery to survive, multiply, and attack more cells of the organism. Otherwise, they are not able to survive for a long time outside of one of their hosts, such as on surfaces or in the air.

The process of infection

Like any other pathogen, viruses can enter the body through respiratory passages, the gastrointestinal tract, the skin, especially when there are wounds, or through sexual contact. Different viruses use different routes of entry. Once inside the body, a virus can spread to certain parts where it can attack specific cells if of course it is not recognized and destroyed by the various lines of defense of our immune system.

Different viruses target the same or different cell types. At a molecular level, viruses interact with the cells by using specific molecules they carry on their capsid or envelope, which can recognize and bind to certain molecules (receptors) on the surface of the host cells. Note that these receptors are not there to let the virus inside. They have different roles that serve cellular functions. However, viruses have evolved so that they can manipulate them for their own favor. This interaction enables the whole virus or just the viral genetic material along with some proteins, to enter the cell and start the process of constructing new virions. It recruits enzymes, ribosomes, tRNAs, amino acids, and more to synthesize large amounts of the viral nucleic acid and proteins. The capsid subunits are assembled, taking the rest of the components inside to create new viral particles. The virions, again, interact with the cell’s plasma membrane to be released from the cell. The viral release may also lead to the death of the host cell. This way, the virus multiplies and can go on and infect more cells and grow even more in numbers.

At any time of this process, the infected individual can help in the transmission of the virus to others since the patients can release viral particles via, for example, respiratory droplets, although you need to remember that not all viruses spread the same way.

Are viruses alive?

From all of the above, we can conclude that viruses are not simple entities. They are very tiny and consist of a very small number of genes compared to their hosts, yet they can hijack them for their own advantage. By doing so, they manage to survive and produce large numbers of copies, often putting their host in danger. But are they considered living creatures? This is a very difficult question that has troubled biologists ever since viruses were first discovered in 1892. The answer is not easy, although most scientists have agreed that viruses should not be considered alive. Has anything changed, though, ever since? Might any new discoveries make them change their mind? What is it that makes us say that something is alive, but something else is not? We need to take a look at seven characteristics that biologists have used to determine life and examine if viruses fall into this category.

All living things must consist of one or more cells comprising of different levels of organization, they must be able to grow, reproduce, metabolize energy, maintain homeostasis, respond to stimuli, and adapt to their environment. At first glance, the answer would be: No, viruses are not living things. They do not consist of cells, instead they use their host’s cellular machinery to construct copies of themselves. Those are assembled but never grow in size or complexity. They do not carry out metabolic reactions or use ATP, and they do not regulate their temperature or other aspects of their internal environment.

Are all these enough for us to claim that they are not alive? How can we be sure that they do not respond to stimuli when not such tests can be easily performed? We also know that viruses adapt to their environment by deciding whether they will replicate inside their host or remain in an inactive state depending on the ability of the cell to carry out the viral reproduction process. Furthermore, viruses constantly evolve through mutations they acquire, which can make them either stronger or weaker. They might not consist of cells, but they are made up of small building blocks that combine, giving rise to more complex structures, such as the capsid. Giant viruses have also been found, whose genetic material includes hundreds of genes, allowing them to be more independent in carrying out protein synthesis and metabolic processes as well.

Therefore, it seems there are still many unanswered questions. The origin of viruses is not known. How did they come to exist in the first place and how are they linked to the other branches of the tree of life? How did their interaction with living organisms result in their evolution? Until we have more answers, viruses will remain things that rely on others to make copies of themselves and will, consequently, be considered non-living.